|

Last Update:

Thursday November 22, 2018

|

| [Home] |

MONITORING OF THE GIANT OTTER POPULATION IN MANU NATIONALPARK IN PERU Until now there had been no long-term investigation of a giant otter population carried out. Therefore we put an emphasis since five years on the annual survey of the entire giant otter population in Manu National park. Giant otters can be distinguished from one another by their throat markings and therefore we are able to include even individuals in our stocktaking (Fig. 1). In 17 oxbow lakes of the Manu river we counted a total of 41 animals in 9 groups. No solitaire otter was seen. Besides we found certain signs (fresh tracks, scats, dens) from one more group. The number of otters along the Manu river is slightly higher than in the previous year.

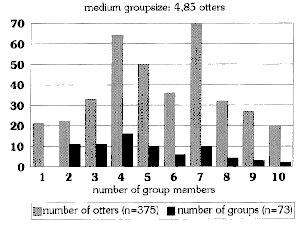

Nevertheless there are still oxbow lakes without an otter group and two groups have not had cubs this year. The total encounter of otters over the past years has now raised up to 375 from 73 groups with an average group size of 4,85 members per group. (Fig. 2)

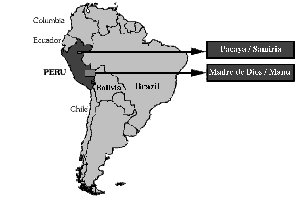

DANGER FOR OTTERS IN PROTECTED AREAS The new survey indicate again that tourism could have a negative effect on the giant otters. At Lake Salvador, where tourism is most intense, we did not observe any offspring this year either - which is an exception among Manu´s otter population. Since three following years we have not seen cubs in this lake. As in previous years, we found otter groups and dens along the river only in the upper part of the Manu river, where no motorboat traffic exists. First investigation to the danger caused by diseases from domestic animals had also been carried out. It is known that typical diseases of cats and dogs such as Parvovirus or distemper can have serious effects on wild animal populations. Giant otter cubs held in captivity have died of Parvovirus and all mustelids are very susceptible to the canine distemper virus. We took blood samples of 16 dogs from the villages from settlers and natives in and around the Manu National Park. Five dogs had Parvovirus antibody concentrations showing an infection and one dog had a significant concentration of distemper antibodies. Domestic diseases could be extremely dangerous for the isolated giant otter populations. Infection could take place also in remote areas: Solitary otters searching for a new partner travel great distances and may control the campsites of several otter groups. Natives travel with their dogs and go to the oxbow lakes for fishing. THE STEPS OF CONSERVATION Also in 1995 the implementation of the conservation plan for giant otters was an important part of the work in Peru. In this context intensive co-operation was going on with the administration of the Manu National park, the ministry in Lima INRENA (Instituto Nacional de Recursos Naturales) and Pro Naturaleza (former name: Fundación Peruana para la Conservación de la Naturaleza - a Peruvian NGO). As part of the conservation plan we presented slide-shows, booklets, posters and information panels to the Peruvian counterparts. For the new rangers in the Manu National Park a three days seminar was held in Pakitza. Profound information of the biology and conservation of giant otters and other important species was offered as well as two excursions. After five years of giant otter research and conservation in Peru a balance sheet was drawn up to see wether suggestions from the project have had any influence to the management of the National Park. Happily the list of implementation of measures is long. The canoe traffic on lake Otorongo has been halted and a provisional observation tower has been built. The otter group at this lake has been reproducing normally since then. Controlled by a permanent park ranger, a prohibited area has been established this year at lake Salvador. The tourism zone of the Manu National Park has not been enlarged and there were no other lakes opened for canoe trips. The control post of Romero is now moved down river to control an important area. The information of tourists and the education of park rangers was improved over the last years. Nevertheless there remains a lot of work to be done to safeguard the giant otter population of Manu. PRELIMINARY SURVEY OF GIANT OTTERS ALONG THE RIO SAMIRIA The third important tropical reserve of Peru (besides Manu National Park and the reserve of Tambopata-Candamo) is located in the Department Loreto in the Northern part of the country: the national reserve of Pacaya-Samiria (Fig. 3). With an area of 21.500 km2, the reserve s even bigger than Manu National Park and has a longer history of human exploitation. Its status permits a certain degree of economic use. Protection of the reserve has improved strongly since two years. The rivers Marañon and Ucayali, which form the Amazon, mark the boundary of this reserve. The main habitat difference is the occurrence of huge areas of flooded forest. Otherwise climate conditions are very similar to the Department Madre de Dios. The survey was carried out in September with the help of Pro Naturaleza, the administration of the reserve and local park rangers. Six lakes, several creeks and about 200 river-kilometers were controlled, but no signs of giant otters could be located. According to all reports by elder local people, giant otters had been common there about 20 years ago. Actual information on giant otters must be interpreted carefully: exaggeration and the tendency to report events of the past as current are common problems, as is the confusion of the giant otter with Lutra longicaudis.

Today it is still possible that sometimes solitaire otters or tiny groups pass through but stable populations of giant otters can no longer be found along the Samiria river mainly due to overhunting and disturbance. Otherwise, the habitat appears to be still intact and ideal for giant otters. The area contains big rivers with oxbow lakes and a network of tiny creeks with sufficient fish. The existence of several hundred river dolphins provides evidence of the latter. Besides the negative result of the first survey along the Samiria river there is safe information that there are still giant otter populations in the Department Loreto. The zoo in Iquitos has a young female which was confiscated from local people and we found two very young cubs in bad conditions in the harbor of Iquitos. The owner of the animals told us that he has bought them from locals at the Puinahua river, closed to the borders of the Pacaya-Samiria Reserve. Further work is very important to locate the last remaining populations and to look for management measures to probably allow recolonisation of still intact habitat. Acknowledgements - The project is financed by the Frankfurt Zoological Society, - Help for Threatened Wildlife - and is carried out in cooperation with the Wildbiologische Gesellschaft München e.V. We like to thank the Peruvian authorities INRENA and the administration of the Manu National Park and the Pacaya-Samiria Reserve for the possibility to carry out the field work. The field work in 1995 was supported by Pro Naturaleza, ALITALIA and the Zoological Society of Philadelphia. |

| [Copyright © 2006 - 2050 IUCN/SSC OSG] | [Home] | [Contact Us] |